Istanbul, June 27

Dear people,

One of my primary objectives when I arrived at Gezi Park almost three weeks ago, was to leave a map of this place, for the historical record. The reason is obvious. Temporary Autonomous Zones are highly evanescent. You have to catch them straight away.

I started my geographical explorations the day after my arrival. Almost a week later, just before the final attack began, I had only just finished mapping the last neighbourhood of downtown. If I had had more time, I could have done a better job, but the amount of data I collected was enough to create a ‘Historical Atlas of Gezi Park’, which I here proudly present to you.

The Atlas consists of six maps.

One is a general overview of the ‘administrative’ subdivisions of the park.

Two is a detailed road map of Gezi Republic with residential zones and infrastructure.

Three is an approximate indication of the various neighbourhoods by their social or political nature.

Four is a map of the greater Gezi Commune with surroundings, suburbs and barricades.

Five is a map of ‘Gezi Empire’, the complete territory in central Istanbul which was conquered by the people in the battles that raged from May 31 to June 3.

Six is a Google map of all known Popular Forums in Istanbul that sprouted up after the eviction of the park.

For a better understanding of the nature of Gezi Park, I will give some background on the maps.

Map 1 – Outline of Gezi Park

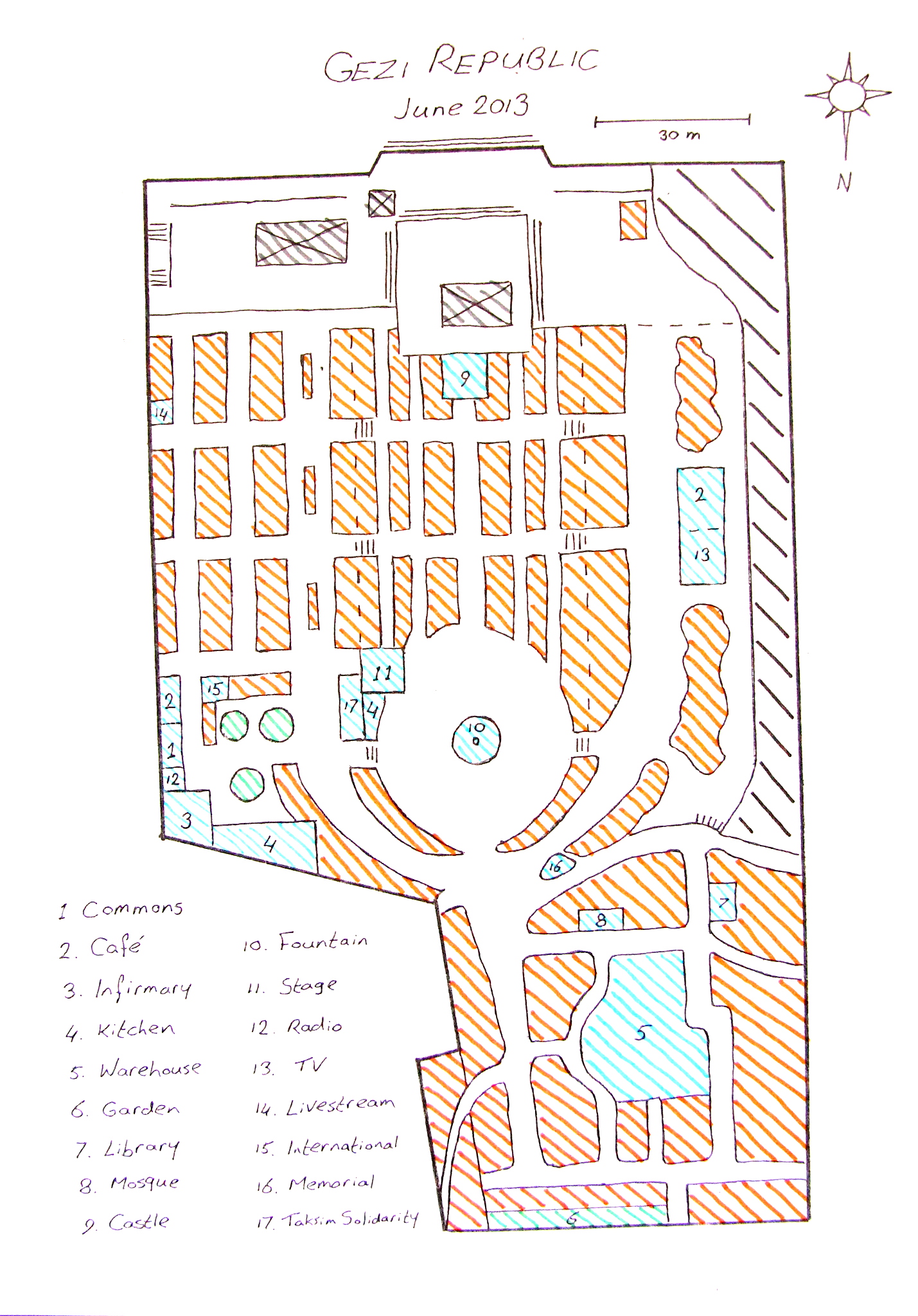

Map 2 – Gezi Republic

Maps one and two

The germ of Gezi Republic, the place where it all began, was at the tip of downtown, in the Gezi Garden (6). This is where a few dozen people from Taksim Solidarity gathered on May 28 to defend the park against destruction. They put up tents. They organized cultural events. They read books in front of riot police.

For three nights in a row, they got peppersprayed and brutally evicted. Their tents were set on fire and the park was fenced off by police. In response to this, the people of Istanbul rose up.

Starting on May 31, a crowd of 100.000+ people marched on Taksim Square from all sides. It was the beginning of a four day battle. On June 1, police retreated from the square. Gezi Park was liberated, and colonization began.

The park is divided into three.

Uptown is made up of the main platform facing Taksim square. It housed almost exclusively political stands and a Kurdish corner.

Midtown features a central rectangle, like a bath tub, flanked by an elevated East and West side. The Central Park was a mix of residential zones and socio-political stands. It’s characterised by the big square with the Fountain (10) and the children’s Castle (9).

The East Side is mainly residential. As a livestreaming collective, we had our base camp on the Upper East Side, at the intersection of Tenth Avenue and Second Street (14). For me personally, my secondary base was the International Corner, which I co-founded on Fourth Street (15). This area, the Lower East Side, was the core of the park, both logistically and politically. It housed the Commons, the Infirmary, the Kitchen, the Çapulçu Cafe and the Radio (1,2,3,4,12). It was also home to the Stage (11), which was controlled by Taksim Solidarity (17).

The West side was dominated by the fixed structured of what used to be a cafe, and what was turned into the Television studio of Çapulçu TV once it was occupied (13). Behind it, there was a natural border in the form a Grand Canyon leading down to the reconstruction site of Taksim square. Compared to the rest of the park, the far West Side was made up of slums.

At the border between the central square and downtown, a Memorial had been erected in honour of those who died (16). It consisted of the text ‘Taksim to the People’, dotted with candles that were lit every evening at nightfall.

Downtown differs from the rest of Gezi Park because of the organic layout of the streets as opposed to the rational Roman/American style city grid in Midtown. The heart of Downtown was entirely taken up by the central Warehouse (5), which collected and distributed all necessary medical, food and other supplies that were donated by the people of Istanbul and the rest of the world. Main features of Downtown, aside from the Victory garden, were the Library (7), built in the form of a fortress, and the Mosque (8), made from two party tents. At the exit of the park behind the Library there was also a subway station.

Map 3 – Gezi Neighbourhoods

Map Three

Much more difficult than plotting the basic structures of the park, is plotting the nature of the neighbourhoods. This has everything to do with the complicated divisions and subdivisions of the Turkish left. My brother Naber tried to explain to me which are the major and minor parties and how they relate to each other, but it’s a mess. You don’t just have communists and socialists, you have marxists, leninists, maoists, stalinists, trotskyists etc. And that’s not even it. You have different sorts of trotskyists, different sorts of leninists, etc. etc. They used to hate each other more than anything else, but they were all together represented at Gezi Park. There’s no point in trying to classify them all. I don’t understand. You wouldn’t understand. And besides, they are all ‘oldthink’. The miracle of Gezi Park was exactly that it went beyond old differences to create a new paradigm.

The communists and the socialists were concentrated mostly in the Central Park, in Uptown and on the Lower West Side. Still, the majority of left wing political stands were located in Taksim Square, until the battle of June 11. The importance of Taksim for the Turkish left wing is enormous, especially since the Taksim Square Massacre on May Day 1977, when snipers opened fire on the crowd from the surrounding buildings and around forty people were killed. Now, during the Gezi Commune, the surrounding buildings were plastered with revolutionary slogans and images of partisan leaders, whose life and memory has always been persecuted by the government.

Even more significant than the presence of the left wing in Gezi Park was the presence of the nationalists. They participated in wide scale resistance against the government for the first time, because they see Erdogan as a danger for the secular Turkish state founded by their iconic hero Mustafa Kemal, ‘Atatürk’. Images of Atatürk, and the Turkish flag, are a fundamental characteristic of the uprising.

There was nationalist presence everywhere in the park. It was curious to see them next to the Mosque in downtown. They also had a small presence in the slums of the Upper West Side, right next to the Kurds. In the final days of Gezi, they colonised the Upper East Side along First Street.

The presence of the (anticapitalist) Muslims in Gezi Park was important to debunk claims by the government that the people in Gezi were no more than a bunch of drunken hooligan terrorists who like to organise bacchanalia in the country’s mosques without taking their shoes off. The Muslims had their political base on the platform in Uptown and their religious base around the Mosque in Downtown.

The Kurds came to Gezi only after their leader Öcalan exhorted them to do so, and then still, they stayed in a corner. For the first time ever they could raise images of their leader without all hell breaking loose. Not everyone in the park was happy with their presence, but nobody made a fuzz about it.

Ecologists, gays and other special interest groups had their main basis in upper Central Park.

Another miracle of Gezi – most astounding for some – was the fact that it brought supporters from the three rival football teams of Istanbul together. Fenerbahçe, Galatasaray and Beşiktaş. They stood as one against police. They stood as one at the barricades. A few weeks earlier, they would have passionately fought each other, and now you could buy t-shirts of ‘Istanbul United’ in the park, with the logos of all three teams.

Finally, the anarchists. They had a strong presence in Downtown, near Gezi gardens, and on the platform in Uptown. But on a subconscious level they embodied the spirit of the park as a whole, for two reasons. One, occupation itself is an anarchist practice, even if it isn’t pronounced. Gezi Park, the Gezi Commune was an anarchist experiment. And two, anarchism is the only political theory that isn’t hopelessly outdated. The communists and the socialists at Gezi Park represented the past. The nationalists and the Muslims represented the present. The anarchists represented the future.

Map 4 – Gezi Commune

Map 5 – Gezi Empire

Maps four and five

The Gezi Republic and Taksim Square were only a small part of the greater Gezi Empire, more commonly known as the ‘Gezi Commune’. The entire area under popular control from June 3 to June 11 went from the end of Istiklal street down to the Beşiktaş stadium and up to the panoramic terrace of the Hilton Hotel.

To picture this, bear in mind the geographical configuration of central Istanbul. Taksim Square is on a hill. And Gezi park is like a fortress on a hill. After the people conquered the square on June 1, clashes with police continued for two more days on the roads leading down to the waterfront. These clashes were spearheaded by Çarşı, the anarchist hard core of the Beşiktaş fans, aided by Kurds and transsexuals.

On June 3, police forces were beaten back to the prime minister’s weekend office in the Dolmabahçe palace on the shore of the Bosphorus. The insurgents conquered one bulldozer, two water cannons and three police buses (which they burned and used as barricades), plus countless shields, gear, gas masks and police cars. In the evening of June 3, the Gezi Commune was a fact.

At its height, the Commune encompassed, at the very least, one university (with two campuses), one high school, two hospitals, one cultural centre, one library, one convention centre, two mosques (not including the one in Gezi Park), two churches, seven consolates (upgraded to full scale embassies for the occasion) and eight luxury hotels.

Suburbs of Gezi park (in light green), with tents or stands, were located in Taksim Square to the south, in the park between the Divan and Hyatt hotels in the north, next to the Technical University in the northeast, and on the hill opposite the Beşiktaş stadium in the east.

The defense of the Gezi Commune depended on the barricades. Three of these were made up of burned police buses. One on the East side of the park, one next to the Intercontinental, where the mobile toilets were placed, and one between the Technical University and the Hyatt hotel.

By far the most barricades, twenty-three lines in total between main and supply barricades, were located on the roads leading down to the sea, where the battle had taken place. Aside from those, all exits to Taksim had been barred, except for Istiklal street. It was a fundamental weak spot in the defense of the Commune, but it was necessary to have a life line through which ambulances, garbage trucks and supply vehicles could enter. To this effect, the barricades on the northeast side could be opened, so that the wounded from the infirmary could be quickly evacuated.

The barricades were manned twenty four hour a day, mostly by anarchist football fans, but also by communists and nationalists. The easternmost suburb of Gezi, opposite the Beşiktaş stadium, was home to dozens of people who acted as an early warning system in case of a police attack from Dolmabahçe palace.

To illustrate how life went on as normal, even in the complete absence of authorities, I will refer a little anecdote as it was told to me by my brother Naber.

One day during the Commune, a distinguished guest of the Intercontinental Hotel had to rush urgently to the airport. Unfortunately for him, the entire Gezi Empire was a traffic free zone because of the barricades. No taxi cabs could arrive at the hotel. The employees of the Intercontinental kindly asked the anarchists on guard to open the barricade so that their guest could leave.

The anarchists refused. In response, the direction of the hotel proposed a deal. “If you open the barricade, we will help you put it back into place afterwards.”

Generally, anarchists are not unreasonable people. They accepted. The barricade was opened. The cab pulled up. The distinguished guest rushed off, and the employees of the Intercontinental Hotel helped to rebuild the barricade on their doorstep.

Map 6 – Popular Forums in Istanbul

Map Six

The Gezi Empire came to an end when police invaded through Istiklal Street on June 11. Another of the luxury hotels, the Divan, aided the protesters by opening their doors to the wounded. For four more days, the people held the park, until the final invasion on Saturday evening, June 15.

In the days that followed, the entire centre of Istanbul was shrouded in tear gas again, and authorities began making mass arrests of the people who had led the resistance two weeks earlier. On June 17, when twenty-two people of Çarşı collective had been arrested in their houses, a small group of citizens came together in the stone theater of Abbasağa park in Beşiktaş to discuss about what to do next.

The day after, their numbers had swollen enough to fill the theater. The day after that, the whole park was cramped with people, and other popular forums were being organized in parks all over Istanbul.

Within a week, Gezi Park was everywhere. I put together all the fifty odd known forums into a Google map, based on the information available on June 25. And this is only the beginning. Just now, a spontaneous assembly popped up on our doorstep…

*αναδημοσίευση από http://postvirtual.wordpress.com/2013/06/27/historical-atlas-of-gezi-park/

Leave a Reply